After a bumpy ride through the barren mountains of Dhofar, we reach a dry wadi (river valley) where resin seeps like blood from a gnarled tree. Ahmed, an incense farmer, carefully uses his knife to cut into the papery trunk and collects the aromatic gum, which dries out into crystals the color of spun sugar.

For millennia, incense has been harvested in this region of Oman and transported to distant places such as Mesopotamia, Rome and India.

The ancient Egyptians used it for mummification, the Magi brought it as one of their gifts, and it played a role in religious rituals worldwide. Hence, its nickname ‘food for the gods’.

I travel with my husband Mark and two children, Zac and Archie, aged 12 and 10, in Dhofar – also known as the Incense Coast – in the far south of the country.

‘In its heyday the trade was worth more than gold,’ says our guide Mussallem, dressed in a long dishdasha, the clothes worn by Omani men, and a tasseled headscarf called a masaar. “Before oil, it was our main export.”

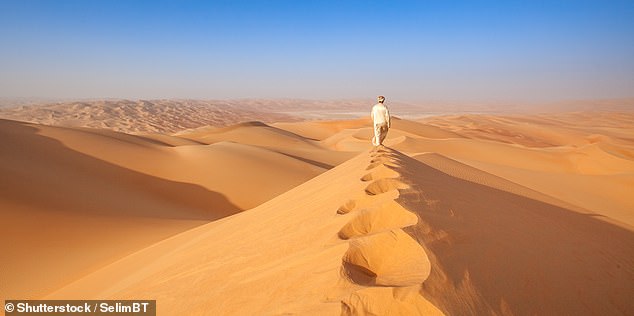

Dune fun: Kate Eshelby and her family travel to the Dhofar region of Oman, where they visit the world’s largest sand desert (file photo)

Later we continue down through deep canyons, past dragon trees that miraculously seem to bloom from the rocks, and desert roses with barbie-pink flowers. Mussallem explains: ‘When we were growing up, there were no roads here, and none of us had shoes. We were still nomadic and lived in caves.’

His family – he has eight children – only settled in a village in 1997, a testament to how recently Oman has changed. “Sultan Qaboos bin Said built the country from nothing,” he continues.

Sultan Qaboos was Oman’s longest-serving leader, ruling until his death in 2020 after coming to power with British backing in a bloodless coup in 1970, which ousted his father. He is honored for transforming the country from an isolated and underdeveloped state into a modern and stable nation.

Qaboos was instrumental in the development of the country we see today – the infrastructure, modernization, education, but also the low buildings. Unlike other countries in the Middle East, there are no skyscrapers or bling.

Oman is home to some brilliant green locations, notes Kate. Pictured is Al Mughsail Salalah

Arriving at Al Fazayah Beach, we run into the warm water as Mussallem lays out hand-woven rugs and cushions under a rocky overhang and sets up a picnic of falafels, chicken samosas, mangoes and salads.

Oman is home to some of the most arid areas on earth, but Dhofar becomes a surprisingly brilliant green oasis during the monsoon months of June to September.

Moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean blow in, creating the surreal sight of cows grazing alongside camels and waterfalls cascading down mountains onto beaches.

In Salalah, Kate stays in a garden villa with a private pool (seen here) at Al Baleed Resort by Anantara

Its near-tropical microclimate means that coconut, banana and papaya trees grow throughout the year. However, it is not just the landscape that sets Dhofar apart, the culture and food also differ from the rest of the country.

The monsoons not only work their magic on land, they also affect the waters, causing upwellings of nutrients along Dhofar’s coast, bringing incredible wealth to the Arabian Sea. There are days when we kayak through clusters of phosphorescence, our oars setting them on fire, making them glow neon like glow-in-the-dark stars. Other times we snorkel among hawksbill turtles, which flock to feed on the colorful corals.

Our journey begins in the capital Muscat and from here we fly to Salalah, Dhofar’s capital, and stay in the Al Baleed Resort at Anantara – a 20-minute drive away, right on the beach.

We are welcomed with small cups of incense infusion and then enter one of the garden villas with a private pool.

Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve (pictured) is one of the last remaining sanctuaries for the critically endangered Arabian leopard, Kate reveals

Kate with sons Zac and Archie in Samhan Nature Reserve, while Zac examines a centipede

Breakfast is eaten while dolphins swim by and early one evening I indulge in an invigorating massage – with frankincense oil, of course – in the spa.

Nearby, rise the fortified ruins of the ancient city of Sumhuram that once stood guard over one of the most important incense ports on the Arabian Peninsula. I imagine the boats coming and going at the height of trade in 3 BC, taking the precious incense east and west, returning with silk, spices and ivory. Meanwhile, camel caravans traveled with it, north across the desert, to the legendary city of Petra.

“According to legend, the Queen of Sheba came here to get incense for King Solomon,” says Mussallem proudly.

Frankincense comes from the Boswellia sacra tree, which thrives wild in the desert areas of the Arabian Peninsula and Horn of Africa – although the best quality is said to come from Oman, with its distinctive aroma. Eventually the old trade routes collapsed due to better shipping and synthetic incense. Yet the tradition lives on in Oman.

Incense remains a cornerstone of daily life, used to perfume homes and clothes and as a symbol of the ever-present Omani hospitality. Walk into any household and you will be greeted by the fragrant smoke rising from an incense burner.

Above, the fortified ruins of the ancient city of Sumhuram that once stood guard over one of the most important incense ports on the Arabian Peninsula. “I imagine the boats coming and going at the height of trade in 3 BC, taking the precious incense east and west, returning with silk, spices and ivory,” writes Kate

Kate explains that Dhofar has a unique climate: ‘Moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean blow in, creating the surreal sight of cows grazing alongside camels and waterfalls flowing down mountains onto beaches’ (file photo)

On another day we venture into the rugged, 4,500 sq km wilderness of the Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve, one of the last remaining sanctuaries for the critically endangered Arabian leopard, high in the Dhofar Mountains. We see Oman’s ever-changing scenery, with acacia trees, more reminiscent of Africa, and elephant baboons, the size of trucks.

As we set off on foot and ascend into this mystical realm of shifting mists and sheer cliffs, we join Khalid, an expert who has worked with the elusive animals for 18 years.

As we wander along a rocky ledge, he shares a recent photo on his phone – of a female leopard and her cub, caught in this very spot with one of the wildlife camera traps. Below is a great view of peaks rising out of the clouds like archipelagos.

The last leg of our journey takes us to Oman’s Empty Quarter, the world’s largest sand desert, north of Dhofar. For this wild camping adventure we are led by Mussallem’s son Mohammed.

On the way we stop at Wadi Dawkah where the luxury perfume house Amouage has created a sanctuary for frankincense trees because these plants are considered almost endangered.

That night we camp in a natural amphitheater of rock, our children excitedly climbing to find their own eyrie-like seats carved into the limestone while dinner is cooked over a fire.

The next day we continue and suddenly the towering dunes appear ahead, the color of ripe apricots and as smooth as sandblasted clay. We set up camp and run barefoot up the sandy spine of one with toboggans in hand, pausing to gaze over a vast ocean of winding ridges before easing back down.

Later, our boys love to see geodes – sparkling with crystals inside – sitting on the sand like soccer balls. While incense may still hold its place in Oman, the country’s golden value now lies in its wild beauty, varied landscape and rich biodiversity.