BBC News, Mahohan and Bots

South African policemen

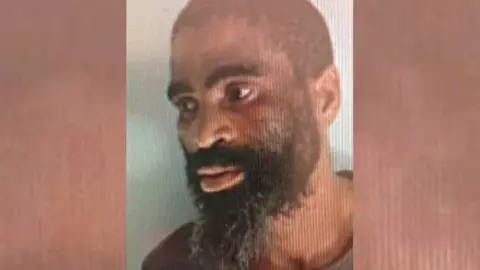

South African policemenNo one in South Africa knows where Tiger is.

A 42 -year -old from neighboring Lesotho, his real name, James Neo Tsoeli, has avoided the police manhunt for the past four months.

Police have alleged that 78 bodies were found under the underground in January after being arrested after being arrested after an allegation of illegal operation in a dropped gold mine near South African Stilfantine.

Four policemen accused of helping his break out and are waiting for bail and trial, but are not close to learning where the authorities are escaped.

We went to Lesotho to learn more about this unavoidable man and hear from those who were affected by the subterranian deaths.

Tiger’s house is located near the city of Mokhotlong, the capital, Maseru, on the road to skirt the mountains of the nation.

We meet her elderly mother Mampho Tsoeli and his younger brother Thabiso.

Unlike Tiger, Thabiso decided to live in the house and the rear sheep instead of joining the so -called Jama Jamaas in South Africa.

Both have never seen Tiger in eight years.

“They are a friendly child for all,” MS said. Tsoeli recalls.

“He was also peaceful at school. His teachers never complained about him. So, in general, he was a good person,” he says.

Thabiso, five years old than Tiger, says he was taking care of the family sheep when he was children.

“He wanted to become a police when we were growing up. It was their dream. But because it never happened, when our father died, he had to become the head of the family.”

Tiger, who was 21 at the time, decided to follow his father’s steps and went to South Africa to work mine – but not in the formal pantheon.

“It was really difficult for me,” says his mother. “I was really worried about him because he was still weak and young at that time. Since he told me to descend into the mine. He used a temporary lift.”

When he got the time or returned for Christmas. And for the first time as Jama Jama, his mother said she was the main supplier of the family.

“He really supported us a lot. He was supporting me. He was giving me everything, even his siblings. They made sure they had clothes and food.”

When his family saw or heard his family last time when Lesotho left Lesotho with his then wife. After a while, the couple separated.

“I thought he could be remarried, and his second wife would not allow him to return home,” she said sadly.

“I’m asking: ‘Where is my son?’

“When he first asked him to be Jama Jama in Stilfantine, I was told by my son. He grabbed his phone and showed me the news on social media and explained that he was saying that he had escaped the police.”

Police say several illegal miners described him as one of the stilfantine ring leaders.

His mother does not believe that he may be in this position and says that he is upset by looking at his scope.

“It really hurts me because I think he dies there, or maybe he’s already dead, or if he is lucky to go back home. I’m not here. I will be in the dead.”

A friend of Stilfantine, who wants to identify only as Ayanda, says that he was sharing food and cigarettes before the supply deteriorated.

He suspects in the “RingLead” label that Tiger is more medium handling.

“He was an underground boss, but he was not a top chief. He was like a supervisor. He could manage the situation we work.”

Mining researcher Makhotla Safuli thought it was unlikely to be at the top of the illegal mining syndicate in Tiger Stilfantine. They say that those in charge of the steward never work underground.

“Illegal mining business is like a pyramid with many grades. We always focus on the lower range. It is the workers. They are underground.

“But there is a second layer … they will supply money to illegal miners.

“Then you got the buyer … they would buy (gold) from those who were supplying money to illegal miners.”

At the top there are “some most powerful” people, “close to top politicians”. These people make more money, but do not dirty their hands in the mines.

Khoyyyanane family

Khoyyyanane familySupong Khaisainane was one of the people at the bottom of the pyramid and they paid their lives.

The 39 -year -old corpse was found in the unused gold mine in January. He had migrated to South Africa like others who were destroyed.

Walking to its village in Thaba-Duseca district, it feels like returning on time.

The journey there is full of obstacles.

After crossing the Ricky Bridge, which is wide enough to hold our car, we are facing mountain roads that do not support the long drive up without safety barriers.

It feels like we don’t lift it up more than once.

But when we do so, the scenery is ancient. Seems untouchable by modernity.

Dozens of small, stone huts, their walls are made of mountainous stone, identifying rolling green hills.

He is an incomplete house that he was building for his wife and three children next to the house of the late Supang’s family.

Unlike most of the village’s dwellings, the house is made of cement, but it has lost the upper roof, windows and doors.

Empty places are a deliberate monument to the person who wants to help his family.

“He left the village because he was struggling,” he said, tells me Mobolokong Khoyasanayana.

Her superb his wife and one of his children slept on the floor on the floor, sadly looking into space.

“He was trying to find money in Stilfantine, to feed his family and put a little roof on his house,” said MS. Says Khoisanayane.

The house was built with the money collected by Supong from a previous work trip to South Africa – many from Lesotho in the decades of the opportunities of the richest neighbors.

His aunt says that her a second time, before leaving three years ago, his employment opportunities do not exist at home.

“It’s so terrible here. That’s why they went out. Because here’s what you can do in small government projects. But you work for a short time. Then it’s.”

This landslide country – completely surrounded by South Africa – is one of the most poor people in the world. Unemployment is 30% but the rate for young people is about 50%, official statistics said.

Supong’s family says he did not know that he was working as a Jama Jama, and a relative would call them until they died in the underground.

He thought he was working on construction and he had not heard from him since he left Babet in 2022.

During the phone call, they were told that the cause of the death of most people in the underworld in Stilfantine was a shortage of food and water. More than 240 people rescued were very sick.

Stilfantine made global highlights at the end of last year when the police implemented a controversial new strategy to crack illegal mining.

According to a South African minister, they have blocked the flow of mine food and water in an attempt to “smoke” workers.

In January, the court order demanded the government to start a rescue operation.

Anadolu through the getty pics

Anadolu through the getty picsThey understand that Supong’s family is illegal what they are doing but they disagree with how the authorities face the situation.

“They were not allowed to send these people hungry. We were really bored that they had been there without food for a long time. We believe that this has ended her life,” says his aunt.

The family of the dead miners finally accepted his body and buried near his half-finished house.

But the mother and brother of the tiger are still waiting for the news about him. South African police say the search continues, although it is not clear whether he is close to finding him.

More BBC stories from South Africa:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC