Scientists have found a new ‘crazy’ life hiding inside our bodies.

They discovered new virus-like objects, called ‘obelisks,’ which are small genetic particles containing one or two genes and forming themselves into rod-like structures.

Obelisks are found in half of the world’s populations, but they were only discovered when researchers looked for patterns that did not match any known species in gene libraries.

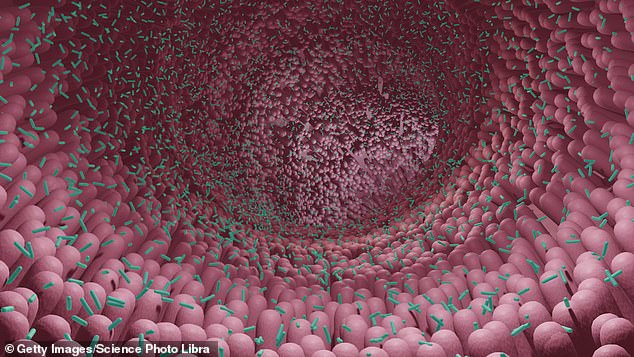

They rule bacteria in the mouth and gut of humansthey live inside them for about a year, but scientists don’t know how they spread.

Obelisks contain genomes of RNA loops that resemble viroids, which are viruses that infect plants, leaving scientists wondering why they were found in human-associated bacteria.

‘It’s crazy,’ Mark Peifer, a cell and developmental scientist who was not involved in the research, said. Science. ‘The more we look, the crazier things we see.’

It is not known whether the monuments are harmful or beneficial, but the group said they can ‘exist as random people.’

Scientists have also suggested that these small, tiny particles may play a major role in the production of the variety of living things that exist on earth todaybecause they can infect organisms of different species throughout their evolution.

Scientists have discovered new life forms called ‘obelisks’ that live inside the bacteria that live in our guts and mouths (STOCK)

Scientists have not yet determined whether these newly discovered organisms can make people sick, but there is one type of viroid that can: Hepatitis D.

Obelisks, viroids and viruses are all technically lifeless creatures that depend on a host to survive. They don’t eat, regenerate or compare.

However, some researchers believe that theviroids and their relatives—perhaps fossils—represent Earth’s oldest ‘living things’.

The research team, led by Stanford biologist Ivan Zheludev, identified the plaques by analyzing data from a database of thousands of RNA samples collected from people’s mouths, intestines and other places.

They analyzed these data to look for single-stranded circular RNA molecules that did not match known viroids and did not encode proteins.

Their research revealed 30,000 different types of monuments. Their genomes have been overlooked in the past because they are so different from any known and previously documented life.

But the findings, published in the journal A cellit shows that monuments do not happen.

Researchers found half of the people in the world have plaques in their mouths, while 7 percent less in their intestines.

Further research will be needed to understand how they are spreading.

The research team identified the obelisks by sifting through data from a database of thousands of RNA samples collected from people’s mouths, intestines and other sources.

The researchers believe that these organisms enter the bacterial cells to replicate, similar to how the HIV virus infects a host and replicates inside.

The types of monuments differed depending on the part of the body that was found and the person from whom it came.

Long-term research showed that one type of obelisk can stay inside a person for about a year.

The researchers believe that these substances enter the bacterial cells to replicate, similar to how the HIV virus infects another person and then replicates inside them.

They found evidence of a microbial relationship to Streptococcus sanguinis, which is a common bacterial component of dental plaque. These little creatures have a kind of obelisk.

This is important because this type of bacteria can be easily grown in the lab, allowing future studies to understand how obelisks survive and replicate in small cells.

All obelisks discovered so far contain a large protein called obulin, and many also contain a second small protein.

Obulins are completely different from all other known proteins, and scientists still do not know their purpose or how they work.

At this point, scientists can only speculate about the evolution and biological functions of Obelisks.

It is possible that they can be destructive and harmful to the cells that store them, but they can be beneficial or not.

If future research shows that the obelisks have a significant effect on the health or function of the human microbiome, that could be important information for human health, experts say.